(Dashboard updates daily M-F)

By Julietta Bisharyan & Mella Bettag

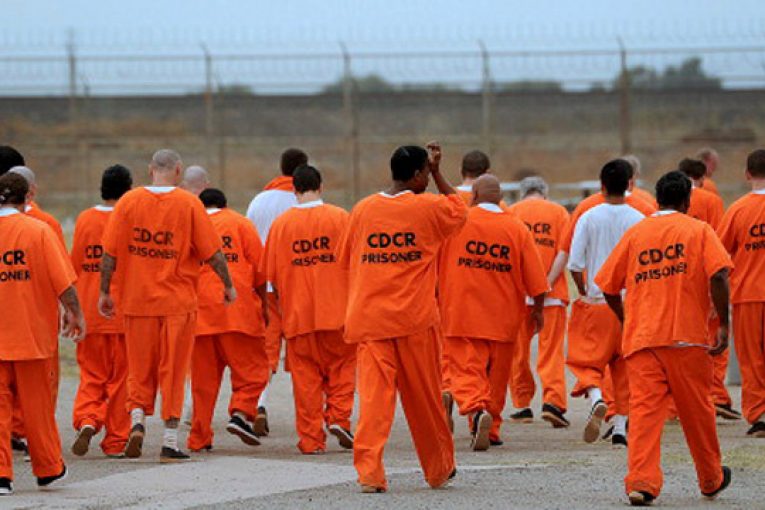

CDCR Confirmed COVID-19 Cases and Outcomes

As of July 31, there are a total of 8,096 confirmed COVID-19 cases in the CDCR facilities, with 1,084 new cases in the past two weeks. 17.8% of the cases are active in custody while 3% have been released while active. There have been 47 deaths system wide with San Quentin Prison (SQ) and CA Institution for Men making up 80%.

There have been five deaths this week at Avenal State Prison (ASP) in Avenal and San Quentin.

One of the individuals is Johnny Avila Jr., 62, who was on San Quentin’s death row since 1995 for two counts of first-degree murder. According to CDCR officials, he died on Sunday at an outside hospital. The coroner is yet to confirm the exact cause of death.

On Jul. 29, Mule Creek State Prison (MCSP) in Ione reported its first 2 cases. 4 facilities (CTF, DVI, PBSP, and VSP) are still yet to report any cases.

At California Institution for Men (CIM) in Chino, the number of active cases decreased by more than half overnight, from 82 to 36. Confirmed active cases at the Substance Abuse Treatment Facility (SATF) in Corcoran also decreased in a day, from 9 to 7.

Only the California Institution for Women (CIW) has tested over 50% of their population in the last two weeks –– testing 1,176 individuals.

50 individuals are currently being treated at facilities outside of CDCR, like local hospitals.

For the first time in three decades the incarcerated population inside California state prisons is below 100,000 persons –– 99,929 as of July 30. The last time the CDCR prison population was below 100,000 was in 1990, when California’s overall population was almost 10 million less than it is today.

Several prisons have shown signs of a second outbreak, like Avénale State Prison (ASP), and California Institution for Women (CIW). After Prison officials at Chuckawalla Valley State Prison (CVSP) failed to isolate Alejandro Cantu, an incarcerated person that was still positive.

Cantu had first tested positive about a month ago. He was tested again after going to the hospital for a broken leg. Six days ago, Cantu’s test came back positive again.

After returning from the hospital, Cantu was placed into a bunk room that housed 11 other men who were negative. The bunks were a few feet away from each other.

Cantu approached a sergeant about his placement, telling them he had just tested positive. In response, Cantu was told “it wasn’t a big deal”.

“I’m concerned about someone getting really sick… I’m concerned about someone dying,” Cantu said about not being isolated. He was also worried about starting a second outbreak, especially after the severe first outbreak in June- nearly 44% of the prison was infected in three weeks alone.

Chuckwalla is overcrowded and cramped. The facility, which was built to house 1,738 people, now holds 2,119. CVSP is at 122% capacity.

As described by Robert McBride, a CVSP resident, the prison is a dry forest in a forest fire.

Currently, there is only 1 active case at CVSP.

CDCR Staff

1,044 CDCR staff members are currently positive with COVID-19, adding to the cumulative staff infection number of 1,791. 747 have returned to work while five have died from COVID-19 related complications.

In the past week, three staff members have died at Central California Women’s Facility, Centinela State Prison and California Correctional Institution.

Effect of CDCR Outbreaks on the Public and Public Response

Throughout the pandemic, healthcare experts have warned prison officials about what would happen when COVID-19 entered the prisons, where social distancing is nearly impossible, many people are struggling from pre-existing health conditions, and sanitation is inadequate.

On July 26th, a group of 757 California healthcare workers signed a letter to Gavin Newsom and CDCR about their position on the handling of the virus within prisons.

As the opening line of the letter, the signatories described their “outrage” at what is happening in the California prisons. “Our slow response to these warnings, both then and now, will be remembered as one of the most flagrant acts of gross medical negligence in our lifetimes.”

In their letter they brought a warning for the future- if CDCR does not release more than half of the prison population, stop all transfers, and follow public health guidelines, more people will die.

The signatories made several suggestions for ways to ensure the health of individual incarcerated people while also lowering the prison population. Their main suggestion? widening the pool of those who are eligible for release.

Currently, the CCHCS qualifications for being at higher risk are much more stringent than CDC guidelines. For example, according to the CCHCS, the BMI at which a person is at higher risk is about 40, whereas according to the CDC, it’s above 30. Also, the CCHCS says those above 65 are at a heightened risk, whereas CDC says those above 50.

Signatories urged CDCR and CCHCS to fix any discrepancy they had with CDC health guidelines.

The letter also has a reminder that “the studies that identified high-risk criteria for complications from COVID-19 were conducted in the general community, and do not encompass forms of risk unique to or heightened in a prison population.” Because of this, signatories concluded, even those without heightened risk should be considered for release.

In regard to releases, signatories also urged CDCR to “prioritize the release of transgender and non-binary people who are at disproportionate risk of harm and violence in prison, and ensure continued and adequate access to hormones before and after their release.” The letter noted that the recent denial of hormones, which are medically necessary, was “unacceptable”.

In regard to lowering infections, the group made two suggestions- halting all transfers and following health guidelines for ethical isolation. Signatories reasoned that if the medical isolation did not feel like the punitive isolation used within CDCR facilities, they would be more likely to report symptoms and get treatment.

The letter also acknowledged the disproportionate incarceration of Black Californians, saying “the State’s failure to respond is an act of racial violence.”

“As healthcare workers, we know that behind each of these data points is a human being. They are fathers, mothers, sons, neighbors, and best friends. They are Californians, and they do not deserve to die.”

Several public defender’s offices have also been advocating for additional releases- more specifically, the release of 21 people from San Quentin (SQ) through Habeas petitions, which argue that being held in SQ right now is cruel and unusual punishment.

To read more about used actions, refer to this article from the Vanguard: https://www.davisvanguard.org/2020/07/efforts-to-release-incarcerated-from-san-quentin-move-forward-in-marin-county-superior-court/.

CDCR Comparisons – California and the US

According to the Marshall Project, California prisons remain third in the country in number of confirmed cases, following Texas and Federal prisons – making up nearly 9.8% of total cases among incarcerated people. California makes up 6% of the total deaths in prison.

There have been at least 1,665 cases of coronavirus reported among prison staff. Three staff members have died while 689 have recovered.

CDCR and CCHCS Precautions

CDCR and CCHCS have not had any significant changes in protocol since last week.

The Department Operations Center, “a central location where CDCR/CCHCS experts monitor information, prepare for known and unknown events, and exchange information centrally in order to make decisions and provide guidance quickly” continues to operate.

All movement between facilities remains halted, including transfers and visitation. Anyone entering the facilities are having temperatures checked and being screened. Masks and sanitizer are provided for all inmates and staff members.

For a general protocol, CDCR is following the Interim Guidance for Health Care and Public Health Providers.

Division of Juvenile Justice

Inside California’s youth prisons, there are about 775 teens and young adults, ranging from ages 14 to 25. As of Jul. 31, 64 of them have tested positive for COVID-19 with 27 cases resolved.

While thousands of incarcerated adults with lower-level offenses have been released early to curb the spread of coronavirus, there have been no plans to release youth offenders early.

Family visitation has been suspended, and all volunteer programs have also been postponed.

Following an outbreak at a youth correctional facility in Ventura County, officials announced that they would no longer be accepting new youth offenders into the Northern California Youth Correctional Complex in Stockton and the Ventura Youth Correctional Facility in Southern California.

The intention of the suspension is to let current active cases of COVID-19 resolve before resuming intakes in the next few weeks.

“Our highest priority is the health and wellness of our youth and staff, and this pause, in cooperation with county courts and probation, will help us accomplish that goal,” Heather Bowlds said in a statement, the acting director of the Department of Juvenile Justice.

Earlier in the year, Governor Gavin Newsom signed an executive order that would transfer the jurisdiction of the state’s Department of Juvenile Justice from the state’s prison system to the Department of Public Health.

The system, which would have been renamed the Department of Youth and Community Restoration, was planned to be in effect by this summer. With the pandemic, however, Newsom extended the deadline until next year.

Later in May, Newsom announced a budget proposal that would shift management of youth offenders to county probation departments instead. County probation chiefs expressed concern about the quick change and not having enough money to expand juvenile detention centers to equip them with the proper rehabilitation programs.

Others have criticized the governor’s plan, believing that the low-funded counties cannot provide the necessary services to rehabilitate troubled teens convicted with serious offenses, such as murder and rape.

“Juvenile halls are not treatment centers,” said Jay Aguas, a former Department of Juvenile Justice deputy director. “They do detention; that’s all they do.”