By Don Chaddock

Inside CDCR Editor / Published in the Mule Creek Post

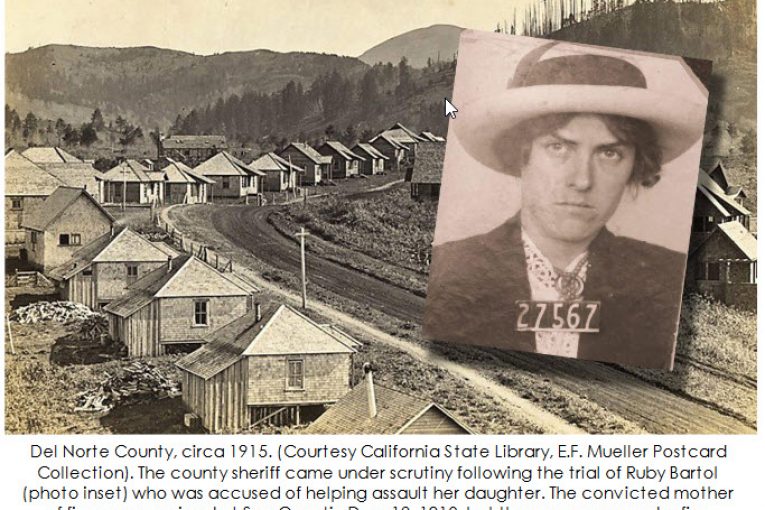

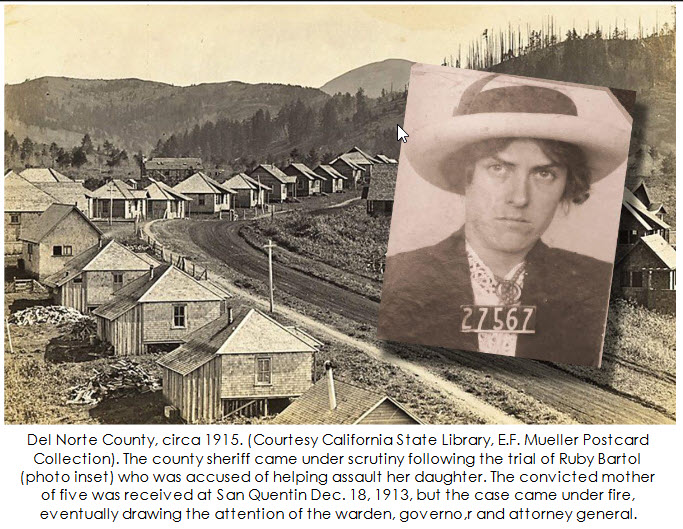

Four people found themselves serving time in San Quentin State Prison in 1913 while another was sent to Folsom after they were convicted of allegedly violating a young girl. The five were eventually released after an investigation found their incarceration had been a miscarriage of justice, according to news accounts at the time.

According to newspaper reports, 30-year-old Ruby Bartol was sentenced to 40 years in prison based on the testimony of her 11-year-old daughter, May. The girl claimed her mother and Mrs. Josephine Horn, 30, held her down while three men violated her. Horn was sentenced to four years while Fred Hoosier received 35 years in Folsom Prison. Two other men also received prison sentences of five years each.

Sheriff A.J. Huffman’s integrity was called into question. During an appeal hearing, the accused men denied anything happened to young May Bartol. One man said he confessed because, “the sheriff said to him that, if he contested the case, he would receive a life sentence. But if he would enter a plea of guilty, he would receive a less severe punishment,” according to the Pacific Reporter, 1914. The courts upheld the original verdict despite the new accusations.

Eventually, May returned to California to testify again, but this time she spoke about the misconduct allegations made against the sheriff and judge. According to the San Francisco Chronicle, April 17, 1915, one of the accused men testified to the state Legislature that the judge knew they were innocent. “I don’t think Judge Childs knew we were all innocent at first, but later, when he found out, he was willing to stand by the Sheriff,” said 23-year-old Otto

Creitzer, one of the men sentenced to five years. He said the group was “set- up” by estranged husband Frank Bartol. The jilted hubby aimed to exact revenge on Orville Taggart, whom he believed to be responsible for breaking up his marriage to Ruby. “The thing was a frame-up. The reason the little girl testified as she did was because the sheriff told her he would send her to jail if she didn’t. (I know) because I heard her tell her mother in front of the jail. We were upstairs and could  overhear,” Creitzer testified.

overhear,” Creitzer testified.

Taggart testified the judge threatened hanging if he didn’t help convict the others. “The judge told me he had enough evidence to hang me and he urged me to do as he advised. He said that unless I did as he directed, he would give me a heavy jolt (at the end of a rope),” Taggart said. “We rehearsed the story I was to tell on the stand against Mrs. Horn. … I told Judge Childs many times that I was innocent.” According to Taggart, the judge told him, “You plead guilty and I’ll give you a five-year sentence and send a personal letter to the warden of San Quentin asking him to take good care of you.” The judge kept his word and sent a letter to Warden Johnston.

Josephine “Josie” Horn, 30, was received Dec. 18, 1914. She was paroled in 1916. Investigating legislator Satterwhite asked why the judge wanted Taggart’s testimony against Horn. “He said that Josie Horn had to be convicted in order to save Sheriff Andy Huffman. She had to be convicted in order to make good the story of Andy Huffman,” replied Taggart. “(The judge) admitted he knew my confession was false. He said he had known me and my family for a long time. ‘I believe you are innocent,’ he said, ‘but I’ve got to stand by Huffman because he stood by me.’”

On May 5, 1915, the Associated Press reported on the judge’s impeachment hearings as the story was picked up across the country. The girl said the sheriff told her to go into graphic detail when she testified. He also allegedly gave her dates to use when detailing the incident. The girl testified in front of the assembly committee in 1915. The April 30 edition of the Sacramento Morning Union called her testimony “startling.” “She (said) she was coached by Sheriff Huffman previous to the trial (urging) her to give false testimony in this respect,” the newspaper reported.

May also admitted her mother, Ruby Bartol, wasn’t home at the time of the alleged attack. The mother had gone to meet a neighbor to collect payment for a cow she sold him. Josephine Horn and two men were home with May and her younger siblings. At the time, Bartol and her husband, Frank, were separated. The girl claimed she heard the men having relations with Horn. She alleges she confronted them and threatened to tell her mother. According to the girl’s story, Horn and the men concocted a plot to put the girl in a situation so embarrassing that they could use it as blackmail to prevent her from telling.

What actually happened, if anything, is unclear but many Del Norte County residents didn’t believe the allegations. “Contrary to the general opinion that prevailed until the last minute, the assembly committee decided tonight not to hold Judge John Childs of Del Norte county for impeachment, following four weeks [of] searching investigation into charges of misconduct filed with the legislature by 37 residents of the northern county,” the AP reported. “The hearing … attracted unusual attention chiefly because of the presence of (the) convicts as witnesses against Childs, who tried their cases. They testified they had been ‘railroaded’ to prison by the jurist. Among the prisoners was Mrs. Ruby Bartol, who was sentenced with four others for an offense against May Bartol.”

The incarcerated people were escorted to the Capitol by Warden James Johnston and prison Matron Jessie Whalen. (Read more about Whalen.) May was brought in from Montana to testify. She saw her mother, but their reunion was anything but cheerful. “The girl’s mother was there awaiting her. Neither displayed any emotion. A stranger never would have known that they were mother and daughter. The short visit they had was painful to both of them. It was terminated by Matron Whalen,” reported the San Francisco Chronicle, April 30, 1915. “While May and her mother were together, Frank Bartol, the husband and father, nervously walked the corridors. …

Finally he was permitted to go into the room where May was (after) Mrs. Bartol … had been taken away.”

The Governor’s office and the state Attorney General began poring over the transcript of the hearing. “The girl testified … that Sheriff Huffman had advised what to tell the court at Crescent City relative to dates on which the attacks occurred and what to say in respect to her debauchery by the men,” reported the Sacramento Union, May 1, 1915. “If credence is placed by the legislative investigating committee on May’s new testimony, there (could) be a movement made to have the prisoners pardoned.” Ruby Bartol denied any wrongdoing and said she had no knowledge of an attack against her daughter. Their sentences were converted to parole in 1916.

May Bartol remained in Montana, but died a few months shy of her 16th birthday. While the cause of death wasn’t listed, it coincides with the 1918 influenza pandemic.

After parole, Bartol remarried and moved to Clovis. She consistently reported to Ed Whyte, the state parole officer, and the local sheriff. Years later, an application for pardon was put in with the governor. She eventually earned a pardon in 1932. She was cleared of a crime she always denied committing and her story ended in 1968 at age 85. According to her obituary notice, she was survived by three sons, a daughter, a dozen grandchildren, and several great grandchildren. Her headstone reads, “Beloved Mother.”