By Fred Johnson and Susan Bassi

In the same week that California lawmakers killed a bill aimed at permitting remote access and recording of family law court cases, a court commissioner denied the Vanguard permission to record and photograph a remote family court hearing assigned to Santa Clara County Superior Court Judge Peter Kirwan. When Vanguard reporters logged on to Microsoft Teams to observe court proceedings related to child support, discovery, and minors counsel, they found Commissioner Jon A. Heaberlin asking for consent to act as a  judicial officer in place of Judge Peter Kerwin who was in the process of retiring. Shortly after obtaining consent to hear a case, Heaberlin was observed allowing a former husband’s divorce attorney to speak longer than other attorneys because the commissioner “knew” and “liked” the attorney.

judicial officer in place of Judge Peter Kerwin who was in the process of retiring. Shortly after obtaining consent to hear a case, Heaberlin was observed allowing a former husband’s divorce attorney to speak longer than other attorneys because the commissioner “knew” and “liked” the attorney.

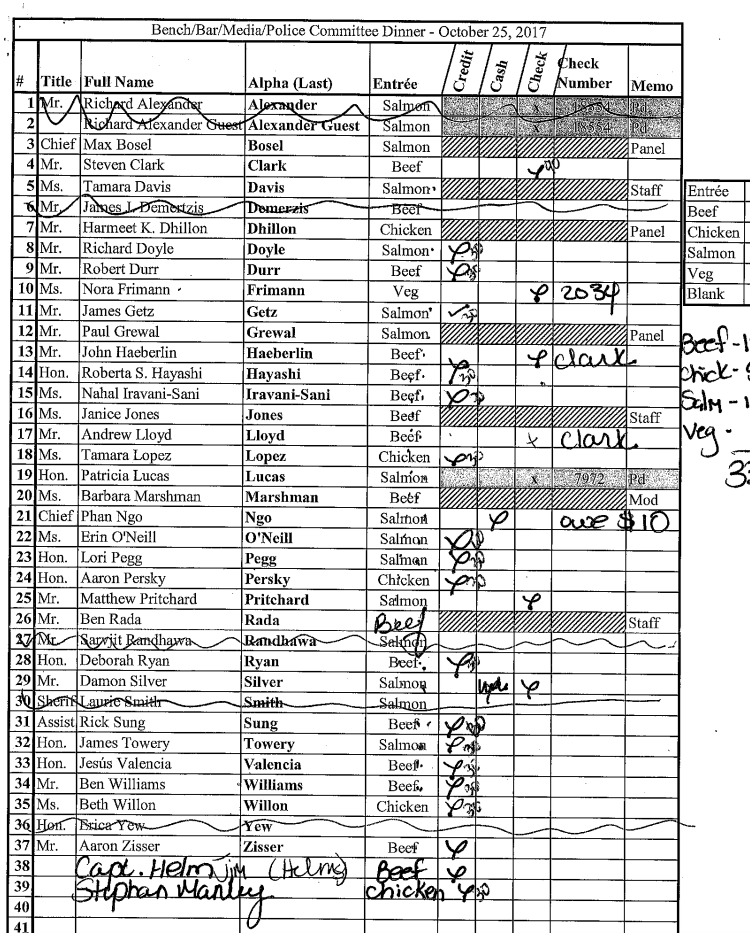

Five years before superior court judges elected him as a court commissioner, John Heaberlin, then a senior partner with the Rankin, Stock, and Heaberlin law firm, attended secreted Santa Clara County Superior Court Bench-Bar-Media-Police Committee (BBMP) meetings previously exposed by The Vanguard. BBMP meetings were held off the record and funded with taxpayer money. In these meetings Heaberlin would have had access not just to attorneys, police officers and judges who would elevate him to the bench, but to San Jose Mercury, NBC and Los Altos Town Crier reporters, the only local media invited to join as BBMP members, as other local reporters were excluded.

Attorneys become judges after they are elected to the bench by voters. Or after they are appointed by the governor. Attorneys who become court commissioners by vote of judges in the local court are far more likely to later become judges through appointment by the Governor. Court commissioners may also move into the lucrative business of arbitration, mediation and private judging.

Consent for Conflicted Commissioners

Parties and lawyers involved in lawsuits, including divorce and custody cases, have a right to have a judge hear and decide their legal issues. However, budget cuts and poor court management have seen more court commissioners assigned to family law and civil harassment cases then ever before. The Vanguard recently reported on a civil harassment case filed by San Jose City Councilmember, Peter Ortiz. A temporary restraining order that outraged First Amendment advocates was granted by Commissioner Thai Van Dat.

At the outset of the court proceedings in late January 2024, Commissioner Haeberlin asked lawyers and parties to agree he could hear their cases, instead of a judge. However, he failed to disclose any conflicts of interest that might raise doubt about his ability to be fair and impartial in those cases.

After participating in BBMP meetings with invited local reporters, police officers, politicians, lawyers and the judges who would later elevate him to the bench, Heaberlin was quick to deny Vanguard reporters the right to record court hearings he ruled in. Vanguard reporters were not invited to the BBMP and were the first to expose it.

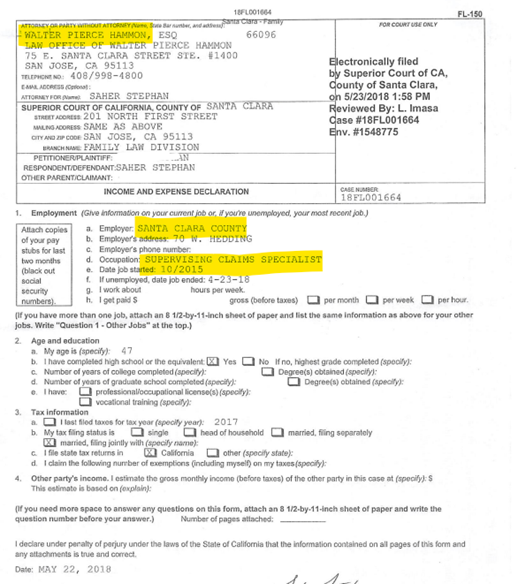

Saher Stephan, a former employee of the Santa Clara County District Attorney’s Victim Services Office, did not make an appearance when his divorce case was called. However, Stephan’s former wife, representing herself, stated she had not received any support since she had begun asking dating back to 2017. That same year Heaberlin was attending BBMP meetings with DA employees and Stephan’s lawyers, Walter and Cory Hammon.

The professional and personal conflicts of interest Haeberlin held with Saher Stephan’s former employer and his attorneys gives an appearance that the commissioner did not act fairly when failing to disclose his BBMP conflicts, and denying the Vanguard’s media request, or right to remotely record the proceedings.

No Right to Record or Access Public Proceedings

California State Senator Susan Rubio recently championed the passage of Piqui’s Law. A law that requires judges to get more training when it comes to domestic violence, and further prohibits family court judges from using reunification camps. Reunification camps are highly traumatic for children and were widely exposed on social media by Maya and Sebastian of Santa Cruz during their parent’s divorce case. However, when it came to championing a bill that would allow not only remote recordings to assist in reducing the costs of pricey transcripts, but help reduce stress, trauma and financial impact of going to court, the bill failed to make it to a lawmaker vote.

Remote court proceedings provide access to public hearings. They also provide an opportunity for reporters, citizen journalists and advocates to access the proceedings in order to document the legal history and educate the public about family court proceedings.

California law prohibits recording of court proceedings, even remote ones, without a court order. Before a judge, or court commissioner rules on the request, the court clerk must notify the parties and their lawyers a request has been made. The judge must also consider several factors before granting or denying the request. The request made to Judge Kirwin, and ruled on by Commissioner Haeberlin, involved a request from divorce attorney to reinstate Nicole Ford as minors counsel in a case involving a 17-year-old child, despite the fact the court would have no authority over the child in less than a year.

In denying The Vanguard’s media request, a commissioner who sat in secret BBMP meetings with invited journalists appears to be perpetuating a culture toxic not only to public trust in the courts, but to the free press and journalists covering the courts.