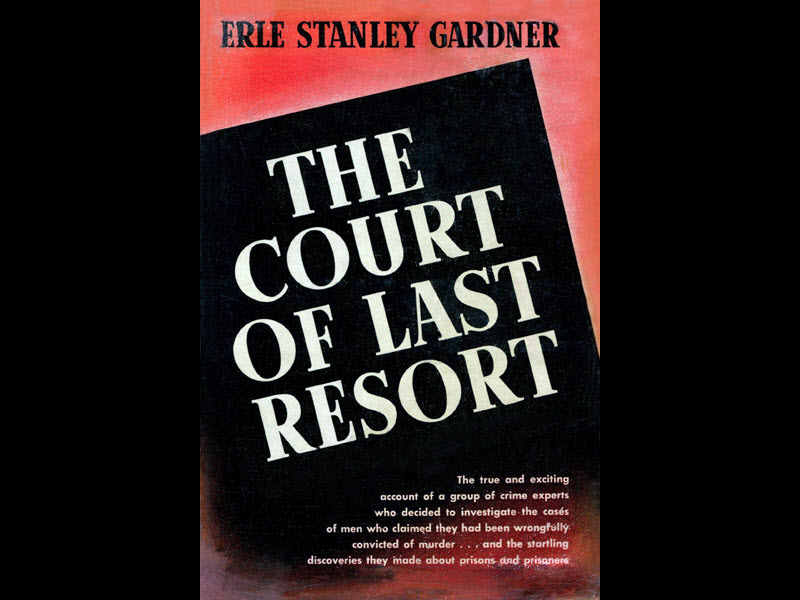

In my reading, I happened upon the book, The Court of Last Resort, written by lawyer-turned-author Erle Stanley Gardner – most notable as being author of the Perry Mason series.

From the late 40s until the late 1950s, he had put together a group of folks from lawyers to retired police officers, investigators, and other professional experts to do what we would today call post-conviction work – re-investigating the cases of dozens of convicts who claimed that they were innocent long after their appeals were exhausted.

They would publish their articles in a monthly magazine, Argosy, for ten years, from September 1948 to 1958.

Gardner got remarkable buy-in from authorities – unlike what we see today. For instance, he would often get officials to halt or delay executions. In one case, Mr. Gardner writes, “Governor Warren, despite any previous statements he may have made, did the right thing and he did it in a decent manner. He promptly commuted the sentence of the defendant to life imprisonment so that there would be an opportunity for a further investigation.”

They would then often get pardons and commutations from governors, and other cooperation.

Even prosecutors. For instance, Mr. Gardner notes that one attorney general was “one of the most fair-minded attorneys general I have ever met.” He notes that the AG decided if the defendant had “been improperly convicted it was up to his office to take the responsibility of conducting an investigation, and this was done with vigor and absolute fairness.”

In another case, the prosecutor Gerald O’Brien was said to be “anxious to convict the guilty” but, at the same time, just as “anxious to see that the innocent are liberated.

“If there is any chance that Louis Gross was wrongfully convicted,” O’Brien said, “my office wants to find it out. If Argosy Magazine is conducting an investigation I will join with it and I’ll do  everything I can at this end. I’ll start investigating right now.”

everything I can at this end. I’ll start investigating right now.”

How far would he go?

Writes Mr. Gardner, he was “convinced that Louis Gross was innocent. Thereupon O’Brien did something that is practically without precedent in the annals of prosecution. He himself went into the Wayne County Circuit Court, and before Judge Thomas F. Maher filed, as the public prosecutor, a motion asking that Louis Gross be granted a new trial.” He said, “As Prosecuting Attorney of Wayne County, I believe it is my duty to protect the innocent as well as prosecute the guilty.”

Today, as we know from countless accounts, AGs, DAs and other prosecutors dig in rather than admit a mistake had been made.

On local news, Mr. Gardner writes, “Without our local newspapers citizens would find themselves in a very sorry plight. I know that in my own case I didn’t fully realize what a powerful factor a newspaper could be in safeguarding liberties until I saw the way these men from the Seattle Times with their knowledge of local conditions could get information that would have been unavailable to us.”

Erle Stanley Gardner didn’t get everything right in his accounts. But the amount he did get right at such an early date was astonishing.

It is perhaps not surprising that we would see the same problems with investigations and prosecutions as today, but it is perhaps surprising that some in the field recognized these problems so early on.

He talked about the torture of a guy in solitary confinement – evidently the man had escaped.

Writes Mr. Gardner: “Solitary confinement is a punishment intended to be meted out to desperate criminals over a period of a few days at a time. A few weeks represents the extreme limit that a man is supposed to be able to endure this form of punishment.”

This man was Vance Hardy: “Vance Hardy was placed in solitary confinement for ten years.” He was “near death” before he was released from solitary, enduring various forms of torture day after day, day after day.

Long before an admonishment, Gardner found problems with forensic methods for determining that two bullets were fired from the same weapon.

He also had good insight. For instance, he wrote that there is a belief that all prisoners will proclaim their innocence and seek to get released.

However, Erle Stanley Gardner found, “Prisoners seem in the aggregate to be far more ethical in such matters than any of us had expected. “ He writes, “When we first discussed the program with penologists they predicted that every prisoner who wanted his freedom, and all of them do, having everything to gain and nothing to lose by appealing to us, would appeal to us in the most heartrending terms possible.”

Instead, he found, “Actually it is interesting to note there is a sense of honor among these men.” They would actually say that they did their crime, but that they would be “suggesting that we investigate the case of some other prisoner.”

I was most impressed with Mr. Gardner’s insight into eyewitness identification and false confessions.

He writes: “It is in the field of eye-witness identification rather than in the field of circumstantial evidence that the most tragic injustices occur.” He even seemed to understand the possibility of contaminated memories: “How much of that identification is predicated upon a recollection of the face of the man who held him up, and how much of it upon the fact that he studied the photograph so carefully that he became familiar with a photographic likeness?”

He doesn’t quite go far enough here.

He writes: “This field of mistaken identification is fruitful of miscarriages of justice. However, if juries are to be distrustful of circumstantial evidence and can’t depend on eyewitness evidence, what can they depend on?”

He responds: “The answer, of course, is that we must accept eyewitness evidence but must be careful to judge the intellectual integrity of the person making an identification.”

Clearly, we know more about how to prevent such mis-identifications today – but the fact that he recognized that at the time is rather remarkable.

He also understood, at least in rudimentary terms, the notion of tunnel vision and confirmation bias.

“The authorities simply closed their minds because they were so convinced this was the culprit,” he writes. “The whole tragedy of errors came to an end when the man who was guilty, harassed by his conscience, surrendered and finally was able to convince the reluctant authorities that he was the guilty person.”

Finally, Gardner assesses false confessions.

“They apprehended the man and finally secured a confession. The man was tried for first-degree murder. The attorney who was representing him was puzzled by the fact that in two respects the man’s confession did not match the physical facts in the case,” he writes.

In another case, “Fowler made several confessions. The first confessions simply weren’t usable. They didn’t conform to the existing facts as the officers knew them and so they were not satisfied with them.” (In the Fowler matter they got four confessions and finally were able to use one of them).

He recognized that “far too many confessions are obtained by physical violence; and there is the question of what, for want of a better name, I shall call ‘mental violence.’”

He didn’t get everything right of course – for instance, he defended prosecutors in a lot of these cases: “Most people lose sight of the fact that it is the sworn duty of the prosecutor to present the case the police have made against the defendant. All too frequently when there has been an erroneous conviction the people blame the prosecutor instead of poor investigative technique.”

For sure police brutality and poor investigation are problems, but so too are prosecutors seeking the win and falling into tunnel vision.

Still, the remarkable thing about reading this book, written in 1958, is how Mr. Gardner recognized huge problems that would vex prosecutors and defendants for the next 50 to 60 years.

—David M. Greenwald reporting

““anxious to convict the guilty” but, at the same time, just as “anxious to see that the innocent are liberated.”

I am wondering when Yolo County is going to elect a DA who meets the above criteria.

You should listen to the podcast posted today – the Florida candidate is way ahead of Yolo

So all those movies and TV shows we’ve seen where a prisoner says “I’m innocent”, and the caps snarks back “Everyone in here says that” . . . are wrong? I’m shocked.

Some also “take the law into their own hands” (e.g., in prison), and commit an additional crime against those whom they deem “deserve it”. Perhaps with what they perceive as the implicit support of society at large.