California has a pretty convoluted system in place due to a number of factors, and a huge amount of money is transferred from the state to local governments. This is in part due to Proposition 13, which makes it very difficult for local governments to raise local revenues.

California has a pretty convoluted system in place due to a number of factors, and a huge amount of money is transferred from the state to local governments. This is in part due to Proposition 13, which makes it very difficult for local governments to raise local revenues.

The problem is that the state, when it is in trouble, starts to raid monies that should be going to local governments. Proposition 22 makes sense after all, since the cities are struggling financially during this downturn, and they should not have the state raid millions of dollars per year from their funds.

So, after more threatened raids, the League of California Cities has sponsored Proposition 22, that would block the state from taking or borrowing local tax dollars. The sponsorship is to protect monies dedicated to cities and counties to fund vital local services like 9-1-1 response, police, sheriff, and fire protection, except that Proposition 22 does nothing of the sort. Instead it protects redevelopment money, which is another animal altogether.

As I was going through the initiatives this weekend, looking at who supported which initiatives, I noticed that most of the newspapers, the teachers, and the Democratic Party were all opposing Prop 22.

That should not come as a surprise to anyone. The LA Times argued, “Proposition 22 would eliminate that flexibility, barring the state from borrowing property taxes or reducing the share received by redevelopment agencies, which finance efforts to reduce blight. It also would funnel fuel taxes into a trust fund that would be all but immune to Sacramento’s meddling.”

Furthermore, “According to the State Legislative Analyst’s Office, the measure would allocate $1 billion more for transportation projects from the general fund and dedicate more local revenue to redevelopment agencies. Diverting fuel taxes out of the general fund, however, would cut the guaranteed funding for schools by an estimated $400 million a year, opponents of the proposition say.”

“It borders on a bait-and-switch to tax voters to pay for something they favor — such as filling potholes — and then use the money for something else. But Proposition 22 goes too far in its efforts to shield transportation and redevelopment projects from the cuts that are shrinking government programs throughout the state,” they write.

So the League of Cities is wrong, the money is not going to vital services, it is going to shielding redevelopment projects and transportation funds, none of which fund the services they claim.

As the LA Times writes, “It’s hard to see why redevelopment agencies’ ever-growing share of local property taxes — 12% statewide by one estimate — is more worthy of protection than school budgets, worker training programs or any of the other public services coming under the knife. Nor does it make sense to force the Legislature to use the general fund instead of fuel tax revenue to pay off existing transportation bonds, as Proposition 22 would do.”

So basically, the legislature last year was able to generate $3.6 billion for education programs by borrowing property taxes and shifting redevelopment dollars.

The California Teachers Association, certainly not a disinterested party in this, argues that Proposition 22 means that schools will lose over $1 billion immediately, plus an additional $400 million every year. That would be the equivalent to 5700 teachers every year.

The billion figure is accurate, according to the Legislative Analyst’s Office. And actually, the CTA may be underestimating the impact projected on a yearly basis.

Writes the LAO, a non-partisan analysis service, “This measure would (1) shift some debt-service costs to the state General Fund and (2) prohibit the General Fund from borrowing fuel tax revenues. As a result, the measure would reduce resources available for the state to spend on other programs, probably by about $1 billion in 2010–11. To balance the budget, the state would have to take other actions to raise revenues and/or decrease spending. Overall, the measure’s immediate fiscal effect would equal about 1 percent of total General Fund spending.”

In the longer-term, they expect, “Limiting the state’s authority to use fuel tax revenues to pay transportation bond costs would increase General Fund costs by about $1 billion annually for the next couple of decades. In addition, the measure’s constraints on state authority to borrow or redirect property tax and redevelopment revenues could result in increased costs or decreased resources available to the General Fund in some years. The total annual fiscal effect from these changes is not possible to determine, but could range from about $1 billion (in most years) to several billion dollars (in some years).”

If the money they were borrowing was coming from cities’ general funds, the proposed limitation might be worthy of at least some consideration. But it is coming from redevelopment, which itself is a bit of an underexplored fiasco.

Redevelopment is a portion of local property taxes that is supposed to be used for blight. But cities like Davis rely on redevelopment money, even in places where there really is no blight.

In fact, a lot of cities have implemented redevelopment, which allows them to draw a larger share of tax revenue than they otherwise would be entitled to in areas where there really is no blight.

For example, back in August the Bee reported on the city of Glendora, whose redevelopment had been ruled illegal, “The other shoe dropped recently when a state appellate court ruled that Glendora’s redevelopment plan is illegal because the city had not proved the existence of urban blight as required by law, upholding a lower court ruling in a lawsuit brought against Glendora by the county of Los Angeles.”

The article continued, “The appeal was pending when Adams’ Glendora bill was enacted last year. The city quickly attempted to use it to fight off the county lawsuit, claiming that, as the appellate decision put it, “the Legislature has now determined that Project Area No. 3 is blighted and entitled to an increased tax increment.”

Furthermore, “The appellate court, however, flatly rejected that assertion, declaring that, no matter what the Legislature said vis-à-vis Glendora, the city still had to prove the existence of blight, which has specific definitions in law, and “in the absence of blight, the redevelopment plan is invalid.”

Proposition 22 would protect redevelopment funds, which in essence are often a way for cities to take more of their share.

The CTA, among others, argue that Proposition 22 would lock the protections for redevelopment agencies into the State Constitution forever. They argue, “These agencies have the power to take your property away with eminent domain. They skim off billions in local property taxes, with much of that money ending up in the hands of local developers. And they do so with no direct voter oversight.”

That probably overstates the problem by a good measure, but not completely. The Redevelopment Agency is the City Council. That means the members are elected by the voters directly, although most voters have little understanding for redevelopment.

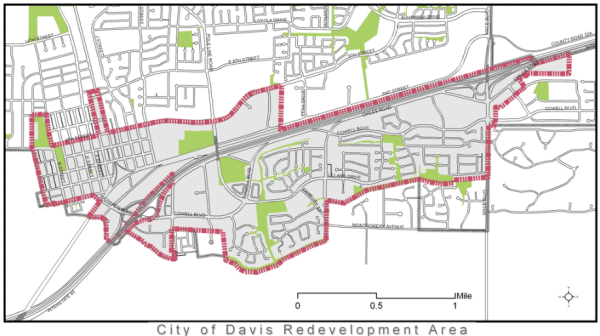

A few months ago I asked City Attorney Harriet Steiner whether Davis’ redevelopment area, which includes the entire core of Davis along with most of South Davis, falls into a legal definition of blight.

Her answer was interesting, “Blight is determined at the time the redevelopment plan is adopted. At the time the Davis Redevelopment Plan was adopted, the City Council made findings that the project area was blighted.”

She continued, “Conditions in the Davis Redevelopment Project Area might or might not constitute blight under current law. However, this does not matter from a legal perspective, because the blight findings are conclusive once the findings are made at the time the plan is adopted and not challenged in court.”

In other words, once the determination is made and they are not challenged in court, the city is entitled to extract redevelopment money.

This is not free money. Because the redevelopment agency includes a huge swath of South Davis, that means that the city’s general fund does not receive property tax money from those areas in South Davis in the redevelopment area.

That should not imply that redevelopment is by itself a bad thing, but it can be abused. The parameters for the Davis Redevelopment Plan were set up in the 1980s and the law has changed, with regards to blight, numerous times since then.

The City of Davis is looking to use the funds from the redevelopment agency to put forth some major downtown projects in the next few years that could be of great benefit.

At the same time, as a state we have to determine our priorities. Cities and local governments have squandered huge amounts of money on unsustainable salaries and benefits. Yes, it is true that redevelopment money is not going into the general fund – although that is certainly a choice of local government, not the state. No one forced cities to divert money into redevelopment.

It is therefore a bit difficult to feel sympathy for local government, when much of their fiscal struggles are in fact self-inflicted.

Therefore, I am now inclined to vote no on this measure, and to hope that cities can find ways to save money by getting their compensation and retirement systems in order, rather than preventing schools from using available monies in the effort to prevent further cuts.

—David M. Greenwald reporting

[quote]cities can find ways to save money by getting their compensation and retirement systems in order rather than [u]preventing schools using available monies to prevent further cuts.[/u][/quote]

Ok… do I understand your point correctly? Cities and ‘local governments’ need to back off “unsustainable” salaries and benefits, to free up money for “education”, which word is often ‘code’ for increasing teachers (and administrators) salaries and benefits?

Teachers in the DJUSD get a guaranteed (in practice) 2.5% increase in salaries for up to 20 years. Local government has at most (in Yolo Co.)

~ 5 pay ranges, 5% apart. In practice, for professionals and other ‘hard to recruit’ positions, agencies need to offer 3rd or 4th step just to get someone “on-board”.

If we ‘protect’ education by adding more money, do you believe that teacher (and administrator) salaries and benefits are ‘sustainable’? Increases in State funding for ‘education’ is likely to drive those costs up.

[quote]Ok… do I understand your point correctly? Cities and ‘local governments’ need to back off “unsustainable” salaries and benefits, to free up money for “education”, which word is often ‘code’ for increasing teachers (and administrators) salaries and benefits?[/quote]

No you do not understand my point. Education has had billions of dollars cut from its budget but the bulk of the state budget goes to local government. They are going to have to share in the cuts as well. It is difficult for me to sympathize with city funds getting raided when they have been so irresponsible with the way they have dealt with compensation issues.

Thanks for the clarification… I still ask, are teacher/administrator salaries/benefits “sustainable”, in your opinion, particularly in Davis?

Teacher salaries are far lower than city staff salaries.

Administrators do make a lot but there are not a lot of them, they’ve cut the number of administrators almost in half. The benefits that they receive pale in comparison to what city workers make. And their retirement plan is a lot less than what city workers get. And they haven’t had a pay increase in five years other than through internal promotions.

David… teachers work ~ 179 instructional days. Based on their pay and benefits, is their compensation “sustainable”? Flat out opinion I’m asking for. Not compared to city employees, Bell criminals, NFL players. Just based on appropriate revenues/taxes.