She told the audience at that the time, “You might think, how could plea bargaining result in wrongful convictions? Isn’t that what defense attorneys are for – to make sure not only that a defendant doesn’t get CONVICTED of a crime he didn’t commit but surely to make sure a defendant doesn’t PLEAD to a crime he didn’t commit!”

“Ideally, yes,” she said. “But OUR criminal justice system is not ideal. Our system is FLAWED.”

She gave the example of the Alford Plea, known because Henry Alford was accused of murder and faced the death penalty, where enough evidence existed that could possibly have been enough to cause a jury to convict him.

“The evidence was strong but Henry said he was innocent. Henry, however, pled guilty to a charge of 2nd degree murder in order to avoid the death penalty,” she said. “Of course, I don’t know as I stand here today whether or not Henry was actually innocent. However, I’ve been a criminal defense attorney in Yolo County since 1998, and I truly believe that innocent people have taken pleas because they felt they were in a situation like Henry’s.”

She said, “Just because the system allows the innocent to plead guilty doesn’t mean that we should tolerate a system that makes it easy to do so… And that’s the type of system we currently have.”

I have been reminded of these remarks twice this weekend.

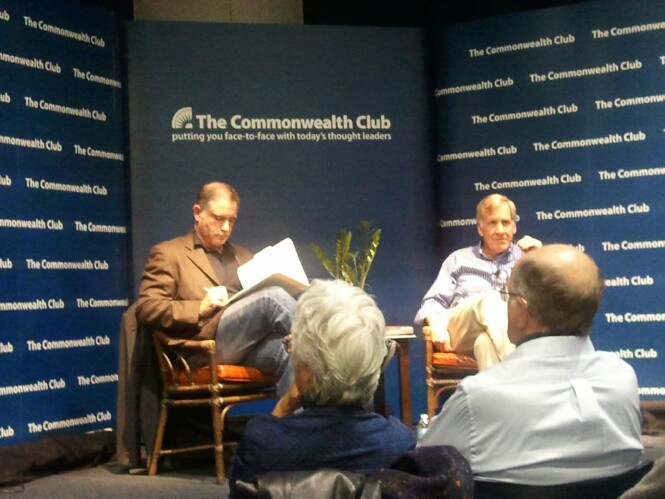

First on Friday, I went to the Commonwealth Club in San Francisco and saw Raymond Bonner (who began as a law professor at UC Davis and ended up a foreign correspondent for the New York Times, covering El Salvador in the 1980s) interviewed about his new book which chronicled the murder trial of Edward Lee Elmore, who served 30 years in prison for a murder he did not commit.

Mr. Elmore was finally released last week, after taking an Alford Plea despite overwhelming evidence of his innocence, in order for him to be released from prison with time served.

That was followed by an op-ed in the New York Times by Michelle Alexander, who formerly worked with the ACLU in Northern California and authored the penetrating book, The New Jim Crow, highlighting how drug laws have created a new segregation and legalized discrimination.

She quotes from Susan Burton, who had recently posed a question, “What would happen if we organized thousands, even hundreds of thousands, of people charged with crimes to refuse to play the game, to refuse to plead out? What if they all insisted on their Sixth Amendment right to trial? Couldn’t we bring the whole system to a halt just like that?”

Ms. Alexander writes, “I was stunned by Susan’s question about plea bargains because she – of all people – knows the risks involved in forcing prosecutors to make cases against people who have been charged with crimes”

She then gets to the crux of her point, “The Bill of Rights guarantees the accused basic safeguards, including the right to be informed of charges against them, to an impartial, fair and speedy jury trial, to cross-examine witnesses and to the assistance of counsel.”

However, she adds, “in this era of mass incarceration – when our nation’s prison population has quintupled in a few decades, partly as a result of the war on drugs and the “get tough” movement – these rights are, for the overwhelming majority of people hauled into courtrooms across America, theoretical.”

More than 90 percent of criminal cases never get before a jury and the vast majority of people charged with crimes will “forfeit their constitutional rights and plead guilty.”

“The truth is that government officials have deliberately engineered the system to ensure that the jury trial system established by the Constitution is seldom used,” said Timothy Lynch, director of the criminal justice project at the libertarian think tank, the Cato Institute.

Ms. Alexander argues: “In the race to incarcerate, politicians champion stiff sentences for nearly all crimes, including harsh mandatory minimum sentences and three-strikes laws; the result is a dramatic power shift, from judges to prosecutors.”

She continues, “The system of mass incarceration depends almost entirely on the cooperation of those it seeks to control. If everyone charged with crimes suddenly exercised his constitutional rights, there would not be enough judges, lawyers or prison cells to deal with the ensuing tsunami of litigation.”

Moreover she points out that not everyone would even need to participate in an organized revolt. Ms. Alexander cites legal scholar Angela J. Davis, who noted, “If the number of people exercising their trial rights suddenly doubled or tripled in some jurisdictions, it would create chaos.”

“Such chaos would force mass incarceration to the top of the agenda for politicians and policy makers, leaving them only two viable options: sharply scale back the number of criminal cases filed (for drug possession, for example) or amend the Constitution (or eviscerate it by judicial ’emergency’ fiat [a binding separation]),” Michelle Alexander writes. “Either action would create a crisis and the system would crash – it could no longer function as it had before. Mass protest would force a public conversation that, to date, we have been content to avoid.”

“As a mother myself, I don’t think there’s anything I wouldn’t plead guilty to if a prosecutor told me that accepting a plea was the only way to get home to my children,” Ms. Alexander said in her conversation with Susan. “I truly can’t imagine risking life imprisonment, so how can I urge others to take that risk – even if it would send shock waves through a fundamentally immoral and unjust system?”

Susan, silent for a while, replied: “I’m not saying we should do it. I’m saying we ought to know that it’s an option. People should understand that simply exercising their rights would shake the foundations of our justice system which works only so long as we accept its terms. As you know, another brutal system of racial and social control once prevailed in this country, and it never would have ended if some people weren’t willing to risk their lives. It would be nice if reasoned argument would do, but as we’ve seen that’s just not the case. So maybe, just maybe, if we truly want to end this system, some of us will have to risk our lives.”

It is an interesting possibility.

—David M. Greenwald reporting

Hmmm…. Very interesting. Thanks.

You’ve neglected to mention an inconvenient truth about lazy defense attorneys/public defenders, who don’t want to be bothered to do the work necessary to take a case to trial, but instead for the lawyer’s own convenience get their clients to cop a plea. See [url]http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/pages/frontline/shows/plea/etc/nyu.html[/url]

[quote]I agree with Professor Schulhofer’s main thesis: The problem of guaranteeing the effective assistance of counsel cannot be solved within a plea bargaining system.1 The reasons for this conclusion fall under two main headings. First, a system of plea negotiation is a catalyst for inadequate representation. It subjects defense attorneys to serious temptations to disregard their clients’ interests, engenders suspicion of betrayal on the part of defendants, and aggravates the harmful impact of inadequate representation when it occurs. Second, a plea negotiation system insulates attorneys from review and often makes it impossible to determine whether inadequate representation has occurred.[/quote]

I know about this bc I had a friend that this happened to…

Elaine: I don’t consider that an inconvenient truth. I consider that part of the problem. In fact, the Innocence Project lists ineffective assistance of council as a chief cause of wrongful convictions, Bonner cited that as a huge problem in the Elmore case. Too many jurisdictions neglect indigent defense. That only thing I would add is that from my observations, it is not a problem in Yolo County. While I’m sure Tracie Olson would love more resources both her department and the conflict counsel do a very good to excellent job of representing their clients.

You also have to consider that people accepting pleas for more severe charges many times. The shoplifter pleading guilty to felony burglary. The trespasser pleading to breaking and entering. The drug user pleading to transportation for sale. The school yard fight being elevated with gang enhancements. Anything to elevate the charge from a misdemeanor to a felony. The person may not be innocent, but the charges do not fit with what they did. But what does it matter, they are told, if all you get is years of probation?

–ERM is so correct!

–At least in years past, Yolo’s defense representation has not been all it should have been.

–More than 25% of CA counties have NO PUBLIC defenders. CA legislation, from 40 or more years ago, allows counties to use private attorneys instead of civil service attorneys.

These private attorneys spend most of their time on their private monied clients and virtually no time on their “indigent” clients.

(“Indigent” covers most people: defense may run about $50,000 and more, for any defense, cash in advance.)

If there’s any county liability involved in a case, the private

attorneys will be “ineffective” or else find their contracts terminated on short notice.

Many defendants don’t know that they don’t actually have a public

civil-service protected defense attorney.

–Olson doesn’t say much about lack of defense funding for good thorough investigation, and expert testing and expert witnesses.

These things are very expensive, and in her conversations with me about a particular young man’s case, she said her office doesn’t have the money.

A couple of things stand out to me.

1. Why has the legislation taken the power away from the judges and given to the prosecution? The judges should be the balance between the prosecution and defense. It seems that the prosecutors can charge however they want, and then offer a plea bargain for a crime that is less than they charged. Overcharge and threaten long sentences–then offer a plea bargain for less time. This is an easy system to abuse and get your conviction rate up.

2. Looking tough on crime helps the prosecutors two ways–politically and financially. These incentives are difficult to overcome without the input from juries and judges.

To FAI: What do you mean by “overcharging”? The DA has the right to charge the defendant with whatever crimes have been committed, and however many crimes have been committed under the law. The DA is not permitted to charge a defendant with any crimes that there is not probable cause for. So you have to define what you mean by “overcharging”.

According to wikipedia:

[quote]In the legal world, in certain instances, overcharging is a practice by which the District Attorney’s office within a given county charges a defendant with criminal charges that exceed what is actually written within the police report pertaining to the defendant’s alleged wrongdoing. The purpose of which is to obtain a plea bargain to a lesser crime in lieu of being convicted of a far more serious crime that was not, in point of fact, ever committed.[/quote]

So am I assuming you have in mind what wikipedia is talking about? (Which makes sense to me…)