On Monday Morgan Poindexter, Caitlin French, Julea Shaw, Rowan Boswell and Aarthi Sekar presented to the Social Services Commission. This evening (Thursday) there will be a similar presentation to the Human Relations Commission.

They told the commission on Monday, “We are a group of Davis residents and researchers with the group Yolo People Power here to share our findings on the Social Determinants of Public Safety which will help inform this commission and the Davis City Council as they seek to re-envision public safety and policing.”

The following is from their slide show and presentation

- The first point of contact with police for which data exists is in the form of calls for service—when citizens dial 911 or non-emergency police numbers and request assistance. We received the call logs for the last 5 years and sorted them into categories which are arranged left to right from least to most severe.

- We found that the vast majority of all service calls are for non-violent incidents with calls about violent crime only accounting for 1.4% of the total. This suggests a large area of opportunity where unarmed first responders may be substituted for traditional armed police officers.

- Of total service calls, check-ups like wellness checks, and mental health checks were nearly 22%. Of these, over 1,000 mental health evaluation requests were made over this 5-year period, suggesting a prime example of an area where trained mental health professionals or unarmed crisis teams and first responders could be utilized.

- To note: Calls specifically pertaining to alcohol/drugs are rare (1.1%), though other call types such as disturbances (i.e. noise complaints) might include overlap with alcohol or drug use. Even still, those calls do not constitute a majority of the public’s requests to police.

- We then obtained the last 5 years of charges (both felonies and misdemeanors) brought by the Davis Police Department to understand what types of crimes are being committed in our city. The general categories on the top of the graph are again arranged left to right by severity. Reminder: Someone can be charged with multiple crimes during a single arrest. Though when we analyzed the data by arrest, the trends were the same.

- When we analyzed the over 5,000 charges, surprisingly we found almost 50% were for alcohol and drug related offenses. 19% were found to be for property crimes such as theft or burglary while only 14.4% were for the most severe crimes, crimes against persons, which include assault and battery, sexual assault, kidnapping, and homicide.

- Comparing the relatively low incidence of alcohol and drug related service calls from the public and the fact that the majority of charges brought by DPD are for substance abuse, it is clear there exists a disconnect between public need and PD response.

- These data give us an idea of what crimes are being committed, and what activities are being criminalized in our city. In other words, possible challenges we face with respect to public safety.

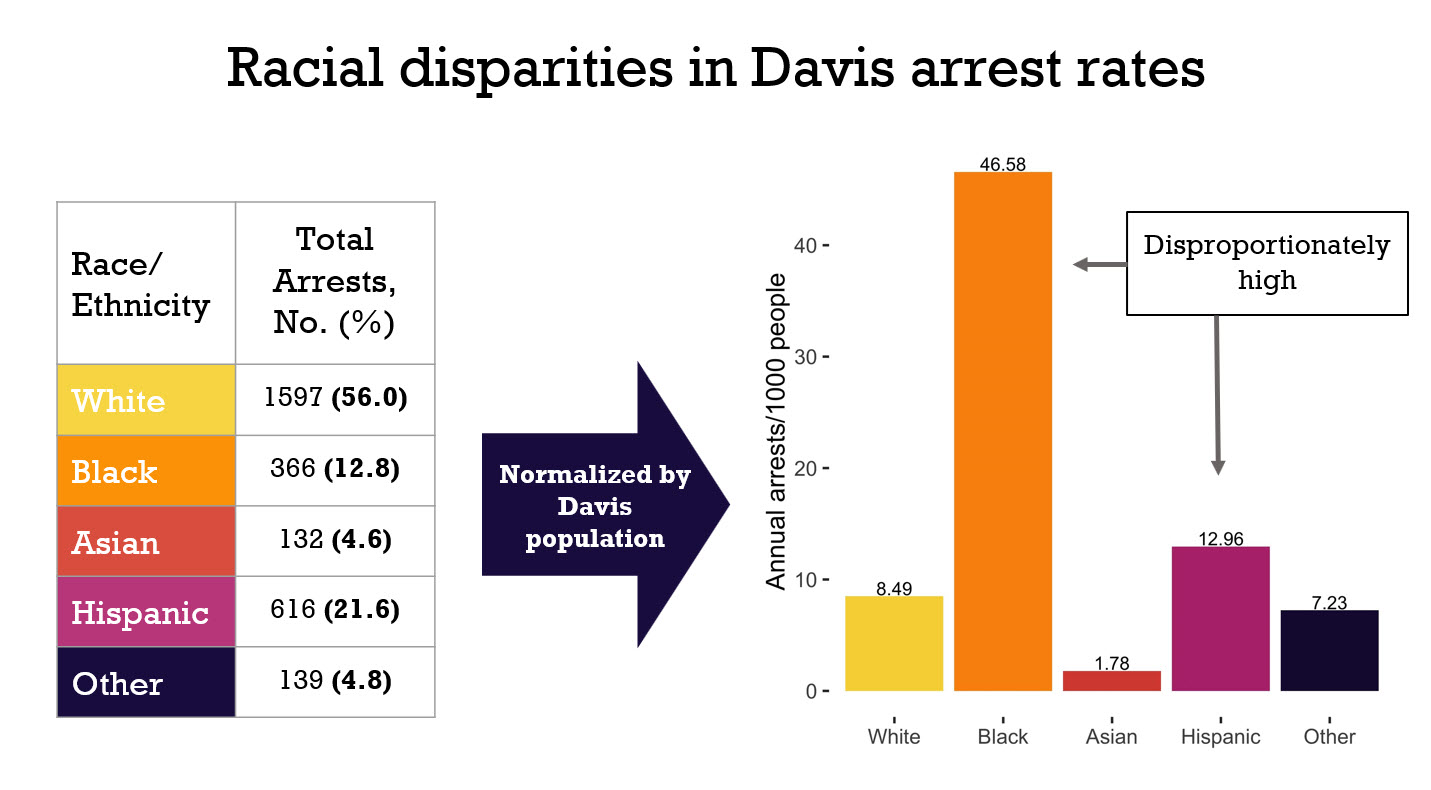

- We also wanted to gain insight into who in our city is actually being arrested to determine if any racial inequities exist. This in particular is important when considering the current national Black Lives Matter movement.

- Using arrest data from the same time period (the last 5 years) we found that the majority of crime is committed by white people in our city which is consistent with the proportion of the population that is white. However, we found stark disparities between the percent Black and Hispanic population of Davis and the percent Black and Hispanic arrests in Davis.

- Normalizing arrests to the population in Davis, we find that arrest rates per 1,000 people are higher for both Black and Hispanic individuals than for white and Asian individuals. Importantly, Black people in Davis are 5.5x more likely to be arrested than white people in Davis. And Hispanic people are 1.5x more likely to be arrested than white people.

- As I wrap up, a quick reminder: arrest rates are not merely a function of crime rates—it is not a direct 1 to 1 connection.

- Importantly, racial biases at multiple levels of police and law enforcement interaction with the public must be considered as possible contributory factors when discussing arrest rates.

- Examples include racially motivated 911 calls, which have made headlines especially in recent years, or overpolicing of lower income neighborhoods which can disproportionately affect non-white individuals.

- Under this framework, our team took a look at existing research to identify the primary social determinants of public safety. In other words, what are the essential building blocks that lead to members of a community feeling and being safe and healthy? We’ve summarized our research so far in this conceptual model on the left that highlights main social determinants.

- You’ll notice that many of these determinants reflect basic necessities and economic security, including access to housing, food, sufficient income, and education, and that many of these also overlap with health and overall wellbeing, highlighting that safety is a part of public health and should be addressed in a similar way.

- An overarching determinant that runs through and intersects with all of these areas is social equity, because inequity in any of these determinants implies that the safety of some are more at risk than others, and also presents threats to public safety as a whole. An easy example of this is to consider how wealth inequality in a community might lead to greater likelihood of theft or burglary.

- We’ve also included anti-racism alongside social equity, because considering the deep historical roots and continuing pervasiveness of racism in our country, any vision for future social equity will require continual proactiveness in dismantling problematic policies and behaviors, likely for generations to come.

- In terms of immediate threats to public safety, we found they fall under two main categories: first, there is crime itself, being committed within communities of civilians against each other, and secondly there are also institutionalized, or legitimized, forms of violence and neglect that threaten the wellbeing of a population.

- Under these two kinds of immediate threats, there are social determinants of each to consider, many of which are overlapping.

- So, what kinds of breaks or failures in the system prevent us from attaining this vision of public safety?

- First, in contrast to our ideal of social equity, social and economic inequities on the basis of skin color, national origin, gender, and sexuality (for example) can manifest in reduced access to income, housing, healthcare, and quality education among affected populations, while at the same time exposing them more frequently to law enforcement and incarceration.

- Ultimately these system breakdowns result in conditions that turn out to be determinants of crime. A few of these examples that we are going to focus on in the context of Davis are substance abuse disorders, lack of housing, and mental health issues.

- These systemic issues also allow for institutionalized harm, such as mass incarceration, to occur. Considering that the institutions charged with addressing public safety can also pose threats to it, we see a feedback loop in which worsening conditions can spark crackdown on crime that in turn can further worsen conditions.

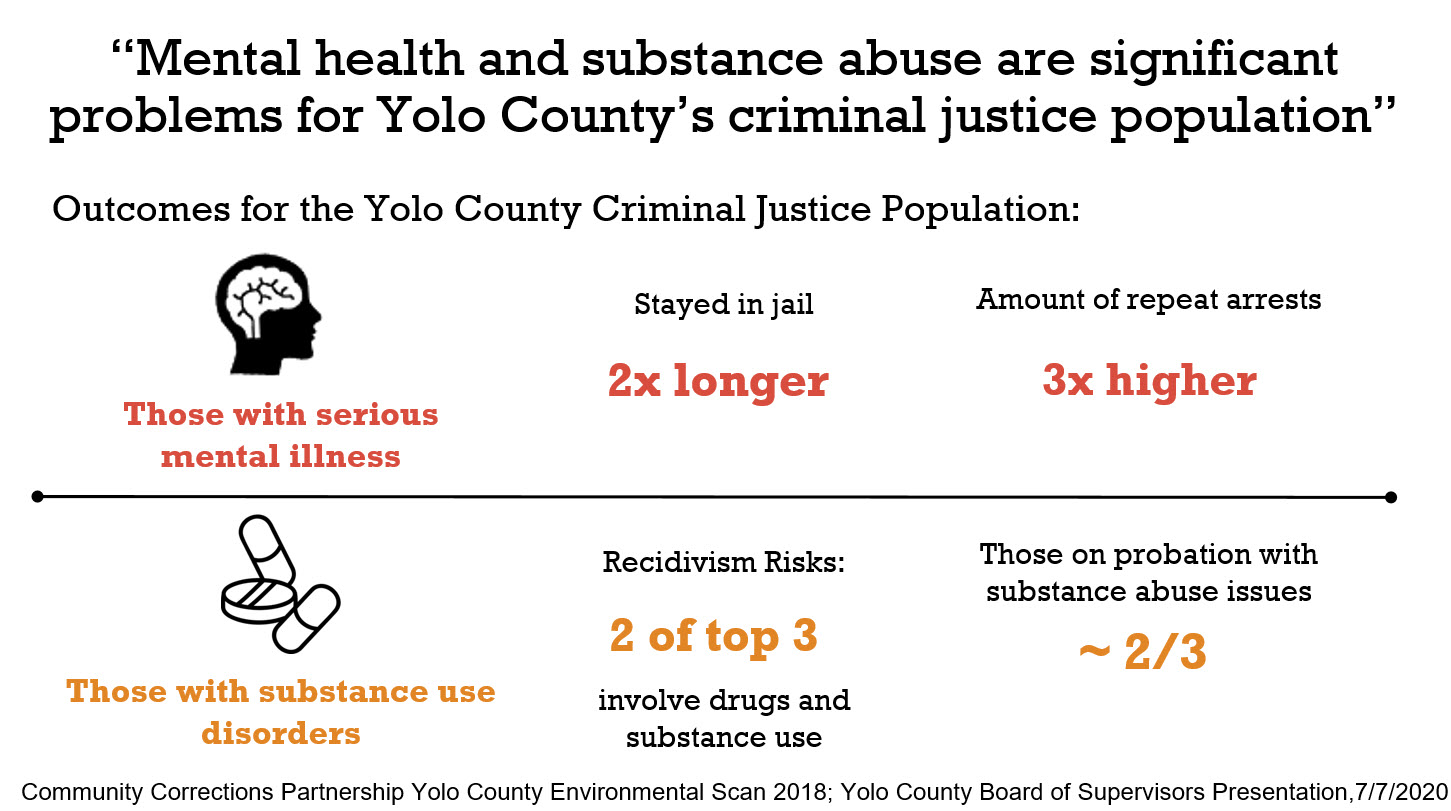

- Taking a closer look at how this feedback loop can play out, we’ve found evidence that criminalization and incarceration as responses to mental illness and substance abuse is in many ways not only ineffective but also potentially harmful.

- Looking at police encounters, a study found that fear of arrest among drug users may hinder them from seeking medical services. In addition, a substantial portion of people killed by police suffered from a mental illness. This raises many questions about how mental illness can better be handled from the standpoint of preventing crime as well as improving de-escalation skills among first responders.

- Looking at incarceration, we find that inmates with serious mental health problems and those with drug dependencies often have limited access to specialized treatment, in particular in jails.

- We see similar issues among houseless populations.

- For example, research has shown that when people are worried about police interactions, they report worse mental health outcomes and sleep habits.

- In addition, being forced to leave more public areas increases risk of exposure-related health issues and of being assaulted.

- And again, contact with law enforcement rarely connected people with services that they are in need of.

- These studies provide support that high police contact and criminalization of homelessness is not an effective strategy, particularly in trying to help those who are most difficult to reach.

- A major social determinant that can affect public safety through multiple pathways is poverty and inequality.

- Looking at Davis, the overall poverty rate is almost 30%; while the non-student poverty rate is 10.32%.The 10.32 is below avg. for CA and Yolo,

- But when we look at median income among the whole population broken down by race, which you can see on the graph on the left, with each color representing a different race or ethnicity and the wider bars representing Davis stats. We see major disparities in our city in terms of income, with white households having higher income than all other groups. And we particularly found when diving further in to the data that Black women are the most negatively affected by this disparity

- We see this racial disparity also reflected in Food stamp data on the right. Where a higher percentage of Black and Hispanic residents are on food stamps than those of other races or ethnicities

- It is important to be aware of these disparities because we know that they can lead to negative outcomes in terms of public safety

- For reference: ((Yolo County Poverty Rate- 19.9%

- California Poverty Rate- 13.4% (source:capradio article (census data, income only))

- National Poverty Rate- 12.9% (source:capradio article (census data, income only)) )

- We also examined some of the negative outcomes we expect to see with a system breakdown. Because such a high percentage of arrests were for substance use, we went and looked at that data on specific drug charges and surprisingly 91.75% of drug-related charges were for personal drug use. So things like possession or public intoxication rather than for sales or distribution. Remember 1/3 of charges brought by DPD are for drug related offenses. So of total charges, personal drug use makes up 32% of TOTAL charges over the last 5 years So this is an indication that we are criminalizing drug use, which we know from the literature is not helpful in aiding those with substance abuse disorders or for helping improve the safety of our community by breaking that substance abuse to prison cycle.

- And we can even see that criminalization of those with serious mental illness or those with substance use disorders is not an effective approach by looking to our Yolo County criminal justice population. We see that those with serious mental health issues have a longer jail stay and are highly likely to be arrested again. And for substance use disorder, we see that those who have finished their sentences still struggle with addiction as seen by the recidivism risks outlined by yolo county where two of the top 3 risks involve access to or use of drugs and that 2 out of 3 people on probation have substance abuse disorders. So again, we are not effectively treating these issues

- And then just really quickly because I know the commission members are familiar with the Yolo Homeless Count. We do have a portion of our homeless population that is frequently homeless, which means homeless on at least 4 separate occasions within the last 3 years. 22% in 2017 and 46.6% in 2019. So this is an indication that the current system is not reaching everyone in need.

- So finally we wanted to show the interactions among the public health and safety challenges that we have been focusing on because they all arise from similar breakdowns in the social determinants of a healthy society.

- So on the left is a graph showing the proportion of the surveyed members of the Davis homeless community who self reported mental health or substance abuse issues. LIST

- We also found that 58.6 percent of those surveyed had been convicted of a crime.

- And finally, among the general public, the National Institute on Drug Abuse reports that over half of those with a mental health issues will suffer from a substance abuse disorder at some point in their lives.

- And we see that all of these outcomes are related and are symptoms of a system that is not functioning like it should be

- We want to reiterate here the high overlap between social determinants and public safety. As was highlighted before, the current punitive approaches are not only inefficient but often harmful to folks who are already vulnerable. So, we did a survey of alternate models to consider for replacing the current approaches. As we surveyed alternative practices across the U.S. that might be employed here in Davis, there were a few value points we kept in mind.

- There were 4 core values that we felt were imperative to keep in mind as we explored other approaches to policing. These include: Social Equity: As the current system exists, there are major restrictions in equal access to resources. Considerations of alternate practices must include discussions on decreasing this equity gap. This also includes increased racial diversity in decision-making processes.

- Another value to consider is Promotion of Wellbeing—actively consider mental health a public safety issue.

- Additionally, working towards a restorative and healing model vs punitive, the value of Proactive vs Reactive. Currently the PD is a reactive system. Public safety issues that arise from inequity and lack of access to resources will never get solved with police response or a punitive justice system.

- And lastly, and very importantly, this work is a shared responsibility. Not only do funds need to be spent proportionally to the need but also response should be proportional to the situation. The Police Department cannot be expected to respond to everything! Let’s expect appropriate funding from appropriate sources. A more responsible way to use community funds would be to put resources towards services that heal and help.

- So, in terms of examples that are relevant to our community, we were able to find great alternative models to gain knowledge from. As we saw earlier, most calls for service here in Davis are not for violent crimes, in fact it’s less than 2%. Programs such as the RIGHT Care program in Parkland Hospital, Dallas TX, responds to people experiencing behavioral health emergencies. Established in 2018, RIGHT Care program is a partnership involving specially trained paramedics from the Dallas Fire-Rescue, officers from the Police Department, and behavioral health social workers. RIGHT care team responds as a coordinated unit to safely and effectively manage patients.

- The RIGHT program has been able to divert 31% of mental health crisis calls and connect patients with community resources.

- This program responds to patients in hospitals and jails, which is why a police officer is on the team. If Davis were to implement a similar program, an armed officer may not even be needed. In one of the programs my teammate Aarthi will present, CAHOOTS, no armed officer is not necessary.

- So our team, in our research, came across several initiatives in terms of alternate policing, which include a handful relevant to California.

- One of which is Assembly Bill 2054 – also known as the Community Response Initiative to Strengthen Emergency Systems Act. AB2054 seeks to address emergency issues such as mental health and substance abuse crises to be addressed in a safer, efficient and more cost-effective manner by encouraging partnership with community organizations that often have deeper knowledge and understanding of the issues. The bill seeks $10 million in funds dedicated for the creation of a dozen or so pilot programs around California that would work to remove police from responses to crises involving mental illness and homelessness, as well as natural disasters and domestic violence.

- Additionally, we would like to highlight that there are a number of cities in California that are moving to promote alternative practices and divert non-violent crises calls away from the police. This includes Alameda County whose program CATT or Community Assessment and Transport Team seeks to implement efforts similar to the RIGHT program at Parkland Hospital, Dallas. Oakland has allocated $1.35 million to a pilot program to these efforts and Mayor London Breed recently announced that San Francisco will implement a program that has trained, unarmed professionals respond to nonviolent crises involving the unhoused or those experiencing mental health crises.

- (Side Note: It would be administered through the state’s Office of Emergency Services.)

- And also, remembering that the most common charge type in Davis is substance abuse, and that in Yolo county, clients with a serious mental illness remain in jail for twice as long with a higher incidence of repeat arrests – it is essential that alternative practices aiming to respond to nonviolent crisis are explored. The CAHOOTS program, in Eugene OR, which has been operating for over 30 years responds to nonviolent crises. CAHOOTS mobilizes two-person teams including a medic and a mental health crisis worker. In 2018 – CAHOOTS responded to 20% of all first responder calls with the response cost at $800,000 while the Eugene Police Department’s overall response cost for the same year was $58 million – saving the City of Eugene a substantial amount in public safety spending annually.

- To summarize and reiterate some important points:

- We’ve seen that punitive approaches to nonviolent crimes are ineffective and unarmed first responders are essential

- We need to relieve burden off of the police

- It is critical that we consider initiatives to address mental health, substance abuse and houselessness

- From our research it seems that one of the most effective things that can be done is for the City of Davis to hire a consultant to advise on restructuring current response methods

- Yolo County Health and Human Services Agency is already working towards hiring a consultant to help with restructuring, and a City of Davis consultant could serve as liaison between the county and the city.

- And lastly – we want to acknowledge the work that the commission is doing – additionally, Davis has a large number of academic researchers and professors who have the tools and skills to survey literature and resources to help with the work and we want to let you know that we are here to do the work and want to support you in doing the work.

To sign up for our new newsletter – Everyday Injustice – https://tinyurl.com/yyultcf9

So I assume in the end the ultimate decision maker is going to be the voting public of each individual municipality each individual City within the county can make their own decision.

I think within this package it should also be noted that all social workers must supply their own burial costs and life insurance policies and shall not be a burden upon the city to plant them in the local cemetery and no statues shall be constructed in their honor.

David – Thanks for posting this information and I look forward to significant discussion on this and future interactions. I would note a few things:

1) It is refreshing to see data being used to inform our thinking on these issues. If we really want to re-envision public health and safety we need to see where the needs are. Policing data is critical because we have allowed the police to become our primary health care first responders. Of course we do not say that but it is exactly what is happening. I don’t think they are equipped and they don’t think they are equipped to play this role.

2. We need to bring fire response data into this analysis as well. We are, arguably, overspending for nearly every emergency response by sending out EMT and fire equipment. That needs to change.

3. As we learn more about trauma as a key part of the social determinants of public health and safety, perhaps we can build in more trauma-informed approaches to response and follow up. That is a programmatic detail, but an important one.

4. Finally, there is a role for non-paid community volunteers in any response. Community health workers are a proven approach to delivering promotional, preventive, and even certain curative services in a community context like Davis. We might think about starting out with a focused “community navigator” role for extended outreach to homeless individuals. I have begun a primer on community health workers here on my blog.