Via Wikimedia Commons

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

By Sabir Rupal

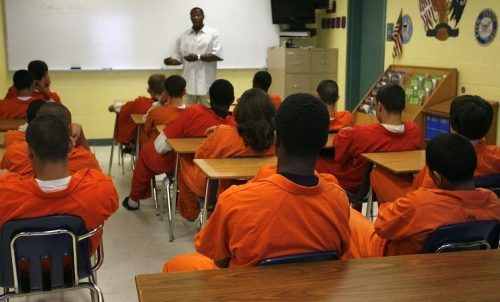

WASHINGTON, DC – Following up on its “Why Youth Incarceration Fails: An Updated Review of the Evidence” report in March, The Sentencing Project has released a new report detailing six “Effective Alternatives to Youth Incarceration.”

Answering the question that the first article posed, “If not incarceration, then what?” this report focuses on programs that can be used to safely supervise youth who have committed serious offenses and are at risk of reoffending or endangering public safety.

While incarceration has been the preferred method for steering young offenders away from delinquency, it has not always received wide-spread support from those intimately familiar with the youth justice system, according to The Sentencing Project.

In fact, the report said it has been nearly three decades since youth justice scholar Barry Feld wrote, “A century of experience with [youth correctional facilities] demonstrates that they constitute the one extensively evaluated and clearly ineffective method to treat delinquents.”

Extensive studies conducted have corroborated his claims, The Sentencing Projects suggests.

“The evidence is clear that incarceration is a failed strategy for reversing delinquent behavior, damages young people’s futures, and disproportionately harms youth of color,” said Richard Mendel, Senior Research Fellow at The Sentencing Project and author of the new report. (PR)

Keeping in line with Mendel’s comments, the report’s highlighted research focuses on several disparate outcomes that come as a consequence of youth incarceration.

These outcomes include: an increased risk of subsequent justice system involvement stemming from pre-trial detention, the impediment of educational and employment opportunities because of a criminal record, the maltreatment and abuse of juveniles and the interference of healthy adolescent development.

These issues only compound when an incarcerated youth comes from an underprivileged ethnic or traumatic background as incarceration often exacerbates their previous trauma and limits their potential access to education and employment, the report noted.

If incarceration is ineffective and not to be preferred, then what alternatives does the youth justice system have to keep juvenile delinquents from reoffending?

Research from the National Academies of Science has found that removing young people from their homes and communities is less effective than a multifaceted community-based approach, even when controlling for “high-risk” adolescents,” the report chronicles.

Taken together, research on and practical experience working within the youth justice system has led researchers to identify six multifaceted intervention models that have demonstrated effectiveness as alternatives to incarceration for youth following adjudication, The Sentencing Project notes.

Those six models include: (1) credible messenger mentoring programs; (2) advocate/mentor programs; (3) family-focused, multidimensional therapy models; (4) cognitive behavioral therapy; (5) restorative justice interventions; and (6) wraparound programs.

The report explains that with an emphasis on community-oriented support, these programs aim to reduce recidivism by addressing common ways to reduce delinquency in minors including cognitive behavioral therapy, mentoring, family counseling and support, positive youth development opportunities (both educational and employment), and restorative justice.

Further, these models have already proved to be effective. The Advocate, Intervene, Mentor Program, or AIM, in New York City is one such program, adds the report.

Started by the deputy director of the New York Department of Probation, Clinton Lacey, AIM is a credible messenger mentoring program that works with 13- to 18-year-old youth on probation who score as “high risk” for reoffense.

Rather than incarcerating young offenders, the report explains, the program provides a “family team” including the youth, family members, probation officer, and a credible messenger—together, they develop an individual plan with goals and related action steps for the young person during the 6- to 9-month AIM program period.

According to The Sentencing Project report, “An evaluation of New York City’s AIM program found that just 20 percent of the participants, all of whom would have been incarcerated if not placed into the AIM program, were incarcerated because of a new offense during the program period.

In the year after enrolling in AIM, 77 percent of participants remained arrest-free and just 11 percent were arrested for a felony. The reoffending rates were far lower for AIM participants than for youth released from facilities before the inception of the AIM program.

The evaluation also found that most AIM participants made significant progress on a range of youth well-being measures, and that success was highly correlated with the amount of time youth spent participating in program activities with their credible messenger mentors,” the report adds.

These results are not just limited to New York—the report mentions programs in other states, including California and Maryland, that have seen similar results when implementing alternative to incarceration models.

Looking ahead, Mendel writes, “Despite a large drop over the past two decades, the number of youth in correctional custody remains far too large. Many significant opportunities remain for state and local youth justice systems to further reduce reliance on incarceration in ways that protect the public and enhance young people’s well-being.

“Pursuing these opportunities—ending the unnecessary, racially unjust, and often abusive confinement of adolescents—should be a top priority of youth justice reform nationwide.”