The launching of the National Registry of Exonerations, a new joint project of the University of Michigan Law School and the Center on Wrongful Convictions at Northwestern University, actually reminds us of just how little we actually know about wrongful convictions, where and when they occur, and how many have occurred.

The launching of the National Registry of Exonerations, a new joint project of the University of Michigan Law School and the Center on Wrongful Convictions at Northwestern University, actually reminds us of just how little we actually know about wrongful convictions, where and when they occur, and how many have occurred.

What we do know ought to alarm and frighten people far more than they are. The reason we are not utterly alarmed on a global scale is that we are comforted by the relatively small number of false convictions.

Michigan Law Professor Samuel Gross and Michael Shafer write in their report, “It is essential to put these numbers in context. No matter how tragic they are, even 2,000 exonerations over 23 years is a tiny number in a country with 2.3 million people in prisons and jails.”

“It used to be that almost all the exonerations we knew about were murder and rape cases. We’re finally beginning to see beyond that,” said Professor Gross said. “This is a sea change.”

“It’s clear that the exonerations we found are the tip of an iceberg,” Professor Gross added. “Most people who are falsely convicted are not exonerated; they serve their time or die in prison. And when they are exonerated, a lot of times it happens quietly, out of public view.”

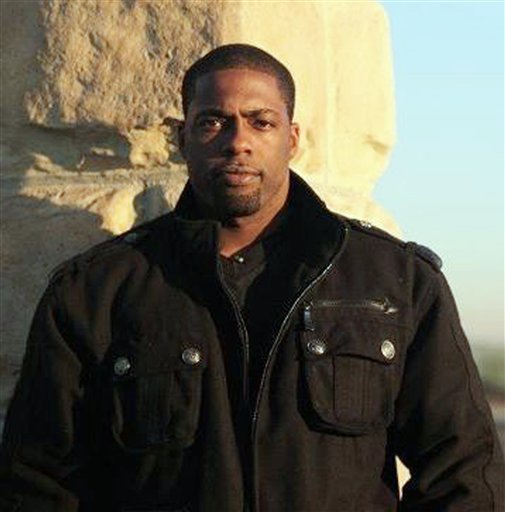

As if by some strange timing, the exoneration this week of Brian Banks drives that point home.

Brian Banks took a plea bargain, despite the fact that there was no physical evidence of the crime.

Without that plea bargain, California Innocence Project Director Justin Brooks wrote last month, “he might have spent the rest of his life in prison even though the case was built on the shaky testimony of his alleged victim, a fellow high school student.”

So he took the deal and went to prison for several years.

But Mr. Banks was lucky.

“All innocence projects are overwhelmed with work. Thus, as directors we must make tough decisions about what cases to take on,” Professor Brooks wrote. He noted that death penalty cases have the highest priority, followed by life and then cases with significant terms.

Most people already released never get their cases reviewed; it’s a hole in the process to even determine how many wrongful convictions there are. Professor Brooks said that they have never taken a case of someone already released from prison.

“There are too few resources. The cases take too much time and too much money,” he said.

“Sex offender cases should be treated differently than other cases. They are life sentences,” he added.

“His situation was so oppressive, where as a convicted sex offender, he’s got an ankle monitor on, he’s got to register, he can’t get work because of his background with the conviction,” said Professor Brooks. “He was just in such a terrible situation, then he shows us this video where we have a clear recantation. It was very compelling and we took the case on.”

In fact, last November Yolo County’s Public Defender Tracie Olson warned of the under-recognized contribution that the plea bargain system plays with wrongful convictions.

In her view, a frequent cause of wrongful convictions in our local system is from the plea bargain process. This is a problem that is perhaps just now starting to get the attention it deserves.

She told the audience at that the time, “You might think, how could plea bargaining result in wrongful convictions? Isn’t that what defense attorneys are for – to make sure not only that a defendant doesn’t get CONVICTED of a crime he didn’t commit but surely to make sure a defendant doesn’t PLEAD to a crime he didn’t commit!”

“Ideally, yes,” she said. “But OUR criminal justice system is not ideal. Our system is FLAWED.”

She gave the example of the Alford Plea, known because Henry Alford was accused of murder and faced the death penalty, where enough evidence existed that could possibly have been enough to cause a jury to convict him.

“The evidence was strong but Henry said he was innocent. Henry, however, pled guilty to a charge of 2nd degree murder in order to avoid the death penalty,” she said. “Of course, I don’t know as I stand here today whether or not Henry was actually innocent. However, I’ve been a criminal defense attorney in Yolo County since 1998, and I truly believe that innocent people have taken pleas because they felt they were in a situation like Henry’s.”

She said, “Just because the system allows the innocent to plead guilty doesn’t mean that we should tolerate a system that makes it easy to do so… And that’s the type of system we currently have.”

While not a problem generally in Yolo County, which possesses a fine system of indigent defense both with the Public Defender’s office and the private attorneys contracted through the county that form the Conflict Panel (for cases such as co-defendant cases where the Public Defender’s Office is conflicted out), ineffective defense counsel remains a large problem.

That likely played a role in Mr. Banks’ case.

H. Elizabeth Harris was a respected attorney who had, perhaps, judicial aspirations.

Alissa Bjerkhoel of the Innocence Project told one media source that Mr. Banks believes “she was on her way out the door of criminal defense and had other plans other than doing private practice… His case was more like she wanted to get it finished and off her plate.”

Mr. Banks claims Ms. Harris scared him into taking the deal.

“You’re a big black teenager and they’re automatically going to assume you are guilty and you’ll be facing 41 years to life. What do you want to do?” he related.

“This is the offer – good for now and not later. It’s your decision and not your mom’s,” Ms. Bjerkhoel said.

Meanwhile, Erwin Chemerinsky, a law professor from UC Irvine said, “Of course the opportunity should exist to talk to his parents before he takes the plea… By itself it’s very offensive.”

Those piling on Ms. Harris forget that, in fact, she may have been right, he may have faced 41 to life and may have been convicted on the basis of his race and size. At least he was able to be parolled in 2008 under the terms of the plea agreement, without which they might have had to seekt a new trial and exonerate him from prison.

The Banks case overall draws into a place that many people do not want to be, recognizing in fact that the number of wrongful convictions is probably far higher than we ever imagined.

The fact is that we only really know a small slice of time, since about 1989. In 1989 there were 11 exonerations. There have been some years with more than 60.

Contrary to popular belief, the majority of those exonerations are not DNA-based.

The research by Professor Gross and Shaffer show that eighty-three percent of known exonerations were in rape and homicide cases – crimes that together constitute just 2% of all felony convictions.

They write, “The problems that cause false convictions are hardly limited to rape and murder. For example, in 47 of the exonerations the defendants were convicted of robbery compared to 203 convictions for rape, even though there is every reason to believe that there are many more false convictions for robbery than for rape.”

In both instances, rape and robbery, “The false convictions we know about are overwhelmingly caused by mistaken eyewitness identifications – a problem that is almost entirely restricted to crimes committed by strangers – and arrests for robberies by strangers are at least several times more common than arrests for rapes by strangers.”

Moreover, unlike in rape, DNA evidence rarely is useful in providing the basis for innocence of robbery defendants.

“Why do so few rape and murder convictions with comparatively light sentences show up among the exonerations?” the researchers ask.

They offer this possibility: “Most innocent defendants with short sentences probably never try to clear their names. They serve their time and do what they can to put the past behind them. If they do seek justice, they are unlikely to find help.”

In fact, they note, “The Center on Wrongful Convictions, for example, tells prisoners who ask for assistance that unless they have at least 10 years remaining on their sentences, the Center will not be able to help them because it is overloaded with cases where the stakes are much higher.”

The Banks case just provides us with enough anecdotal evidence to bely their point.

That is the reason why we look so closely at capital murder cases like Carlos DeLuna because they are able to provide us with so much insight into the system.

Capital cases, frankly, should have a lower error rate than other cases. In most states, there is a multi-step process where there is a guilt and penalty phase. In California for example, the defense gets two attorneys, and more budget for investigations. There are automatic appeals that should lengthen the process and mitigate the possibility of error.

And yet, Don Heller, the former prosecutor who authored the 1978 death penalty bill, believes that at least one of the 13 people that California has executed under his law was innocent.

“I believe that Tommy Thompson was innocent of the rape-murder that he was convicted of and sentenced to death,” Mr. Heller said in response to a question from the Vanguard. “Thompson’s case relied almost exclusively on the testimony of an informant, aptly named Mr. Fink.”

“Mr. Fink was a professional informant, he had actually put several people on death row by people confessing to him in jail and it just so happened that Mr. Fink always benefitted from this confession that was made to him,” Mr. Heller continued.

“I think that Tommy Thompson was innocent,” he said. “He was executed under the law I wrote and that has stayed with me since 1998 that I participated in the execution of an innocent man.”

Mr. Heller said, in a Los Angeles Times interview last spring, that the Tommy Thompson execution marked a turning point for him.

“It took the Tommy Thompson execution [in 1998] for me to become very vocal. It was an example of a clear abuse of the death penalty law,” he said.

He explained, “In the co-defendant’s trial, the prosecutor switched theories. It was no longer Thompson as the rapist-murderer but the accomplice. While you can aid and abet to qualify for the death penalty, an accomplice must have the intent to kill to be death-penalty eligible.”

“The co-defendant accomplice was convicted of 2nd-degree murder, but the prosecutor made no effort to notify Thompson’s trial judge that evidence now showed that Thompson was not the actual murderer. The trial judge has the authority to rectify an erroneous judgment,” he said.

While the issue was raised on habeas corpus, ultimately the U.S. Supreme Court upheld the conviction on a technicality.

Back in 1998, Dorothy Ehrlich of KQED reported Mr. Heller’s words: “I was contacted by Thompson’s appellate lawyer about testifying at a clemency hearing. I laid out in detail the reasons that I felt this was wrong, that it violated the letter and spirit of the initiative, the fundamental law, the prosecutor’s obligation, and was an injustice. Gov. Wilson refused to commute his sentence. In 1998, Thompson was executed. I’ve been a vocal advocate in favor of abolition ever since.”

“Thomas Thompson’s case was surely remarkable. He was executed for a crime that we doubt he committed. A man prison officials described as a model prisoner, he not only had no criminal record, he had never even been arrested.”

“The federal district court was convinced that his trial lawyer had botched his case and that Thompson was erroneously convicted of capital murder. The 9th Circuit Court of Appeals ultimately agreed with this ruling, but unfortunately it missed its own procedural deadline for deciding the case.”

Ms. Ehrlich reported, “It was on this basis, the court missing its own deadline, that the U.S. Supreme Court reinstated Thompson’s death sentence. Thus Thomas Thompson may be the only person ever executed as a result of acknowledged judicial malpractice. And in the court of public opinion, sincere concern about Thompson’s guilt drowned in this morass of complex legal procedures.”

If California can execute an innocent person despite all of the protections that exist, how many others havr been wrongfully convicted but not exonerated?

The DeLuna case in Texas proves more troubling because of the speed at which Mr. DeLuna would be executed, just six years after the fact.

After the fact, researchers have been able to string together issues that should have raised the alarm.

Andrew Cohen in the Atlantic created a ten-fold list of things that should have been raised and answered prior to Mr. DeLunda’s 1989 execution:

1. There was no DNA or blood evidence on DeLuna despite bloody murder scene. There were no fingerprints. There was only one eyewitness and he was sketchy about what he had seen.

2. Police/prosecutors knew the whereabouts of another, more likely, suspect. But they didn’t tell the defense this before or after the trial.

3. When the defendant identified the likely killer shortly before trial, the police and prosecutors did not reasonably follow up even though they knew that the man identified was capable of committing the crime.

4. Based upon early witness reports, the police at first sought another suspect. They did not share this information with the defense even though the two men (the two Carloses) looked eerily like one another.

5. The police officer collecting witness accounts relayed inaccurate and incomplete descriptions of suspects to the police dispatcher, who radioed them to officers in manhunt.

6. Police investigators botched the crime scene by turning it back to the store manager just two hours after the murder to be washed down and reopened immediately.

7. Evidence from the initial investigation was checked out by a prosecutor the day after the trial and was never returned. Any usuable DNA thus was lost.

8. The trial judge appointed a solo civil practitioner without any criminal trial experience, much less any capital trial experience. The defense did not call a single “mitigating” witness in the sentencing phase of trial.

9. Police investigators did not measure a bloody footprint they photographed at the scene of the crime or test a cigarette butt they found on the floor of the store where the victim died.

10. A 9-1-1 dispatcher failed to quickly dispatch police to the scene of the crime, despite the fact that the victim had called for help. Later, the “manhunt tape” made by dispatchers was taped over and not turned over to the defense by the police.

The problem that we face is that these kinds of problems probably exist quite frequently. We see frequent errors by crime labs, established procedures that turn out to be based on junk science, and incompetence in general.

People who support the death penalty want to argue that we could streamline the system and move it through faster, but not without creating more errors and more innocent people getting executed.

The fact is that it is difficult to establish a system that safeguards these problems. After all, we want to trust the jury but the jury gets cases wrong like DeLuna. We want to trust appellate courts, but they get things wrong. We want to trust the Supreme Court, but they get things wrong.

The fact is, most exonerations happen twenty years after the fact, when errors are fully investigated, new technologies become available, or people who were pressured into wrongful testimony recant.

We cannot turn back time, but if we do not execute the individuals, at least we can restore their lives.

Mr. Banks is only 26, and he still has his entire life in front of him.

As often as the professors point out, “The tragedies are not limited to the exonerated defendants themselves, or to their families and friends. In most cases they were convicted of vicious crimes in which other innocent victims were killed or brutalized. Many of the victims who survived were traumatized all over again, years later, when they learned that the criminal who had attacked them had not been caught and punished after all, and that they themselves may have played a role in condemning an innocent person. In many cases, the real criminals went on to rape or kill other victims, while the innocent defendants remained in prison.”

—David M. Greenwald reporting

[quote]Those piling on Ms. Harris forget that, in fact, she may have been right, he may have faced 41 to life and may have been convicted on the basis of his race and size. At least he was able to be parolled in 2008 under the terms of the plea agreement, without which they might have had to seekt a new trial and exonerate him from prison.[/quote]

It takes a lot less effort and expenditure of $$$ by the public defender’s office if the defendant takes a plea deal, than if the case goes to trial. This in my opinion represents an extreme built in conflict of interest in regard to plea deals…

I’m not sure how much evidence they could have had to convince Mr. Banks (and his attorney) that it possibly could put him in prison for longer that his nolo plea got him–considering that he didn’t do it. In this situation, nolo was the next best thing to a confession.

“Those piling on Ms. Harris forget that, in fact, she may have been right, he may have faced 41 to life and may have been convicted on the basis of his race and size. At least he was able to be parolled in 2008 under the terms of the plea agreement, without which they might have had to seekt a new trial and exonerate him from prison.”

Wrong! Ms. Harris deserves all the piling on she might be getting and then some. To say that a known innocent person “might” have been wrongfully convicted without evidence because of his race and size is no reason to plea bargain. The justice system–requiring guilt beyond reasonable doubt–is not that flawed, certainly not enough to excuse Ms. Harris’ actions in the slightest.

Plea bargains are there to benefit people who are guilty as well as society, not to screw the innocent. Find one public defender (or even a less honorable, run-of the-mill defense attorney) who will tell that you there’s a single situation where he or she would intentionally have an uninvolved, innocent person accept such a deal, and I’ll reconsider.

If she represented Mr. Banks by convincing him to agree to a nolo plea, a conviction and a prison term knowing that he wasn’t involved whatsoever, she’s scum and deserves quick, certain and heavy-duty justice. Don’t try to lessen her crime by saying the system is the problem here when it’s really one severely defective person who had no business being an attorney.

[quote]Plea bargains are there to benefit people who are guilty as well as society, not to screw the innocent. Find one public defender (or even a less honorable, run-of the-mill defense attorney) who will tell that you there’s a single situation where he or she would intentionally have an uninvolved, innocent person accept such a deal, and I’ll reconsider. [/quote]

It happens all the time to save effort and $$$… the Public Defender’s Office just won’t admit it…

Pingback: Thirteen Exonerees Already This Year: The Registry Keeps Count | Innocence Project of Florida